I joined Veepee as VP Engineering after leaving a Senior Engineering Manager role at Docker in mid 2017 with the goal of learning what it takes, and testing my own capabilities, to lead a large scale engineering group. What started as a journey as VP Engineering over a Paris-based organization of 180 ended as Deputy CTO over a European-wide group of 900. There’s no way I could document all the learnings at once, so I’ll start at the very beginning and the first surprises.

Structuring an organization

The first 6 months were what anybody would expect: lots of observation to understand the system and its dynamics, defining a healthy organization based on clear roles and expectations, setting a frame for our technical identity, and ultimately establishing our culture as a department. Perhaps I should have known better, and a more experienced leader likely would have seen the writings on the wall: two things rapidly came to me as a surprise.

One pleasant surprise was that the structuring phase wasn’t as hard as I imagined it to be. The goodwill of the team I was lucky to lead certainly contributed to it, and the experience would have been vastly different with an initially change-averse structure. While all the fundamentals are crucial to get right, they thankfully have been covered extensively by people way more capable than I am. You need a solid mix of:

- Experiences: not just your own, but more importantly the shared learnings of those in similar positions before you (and I can’t invite you enough to follow the links above).

- Empathy: no amount of experience is a substitute for context and no two teams are equal.

- Support from your hierarchy.

The good news is that all of these ingredients are in your hands. The surprise that did however hit hard is the realization that leveraging this organization into fulfilling its true potential was where the real challenges lied.

Understanding our bottlenecks

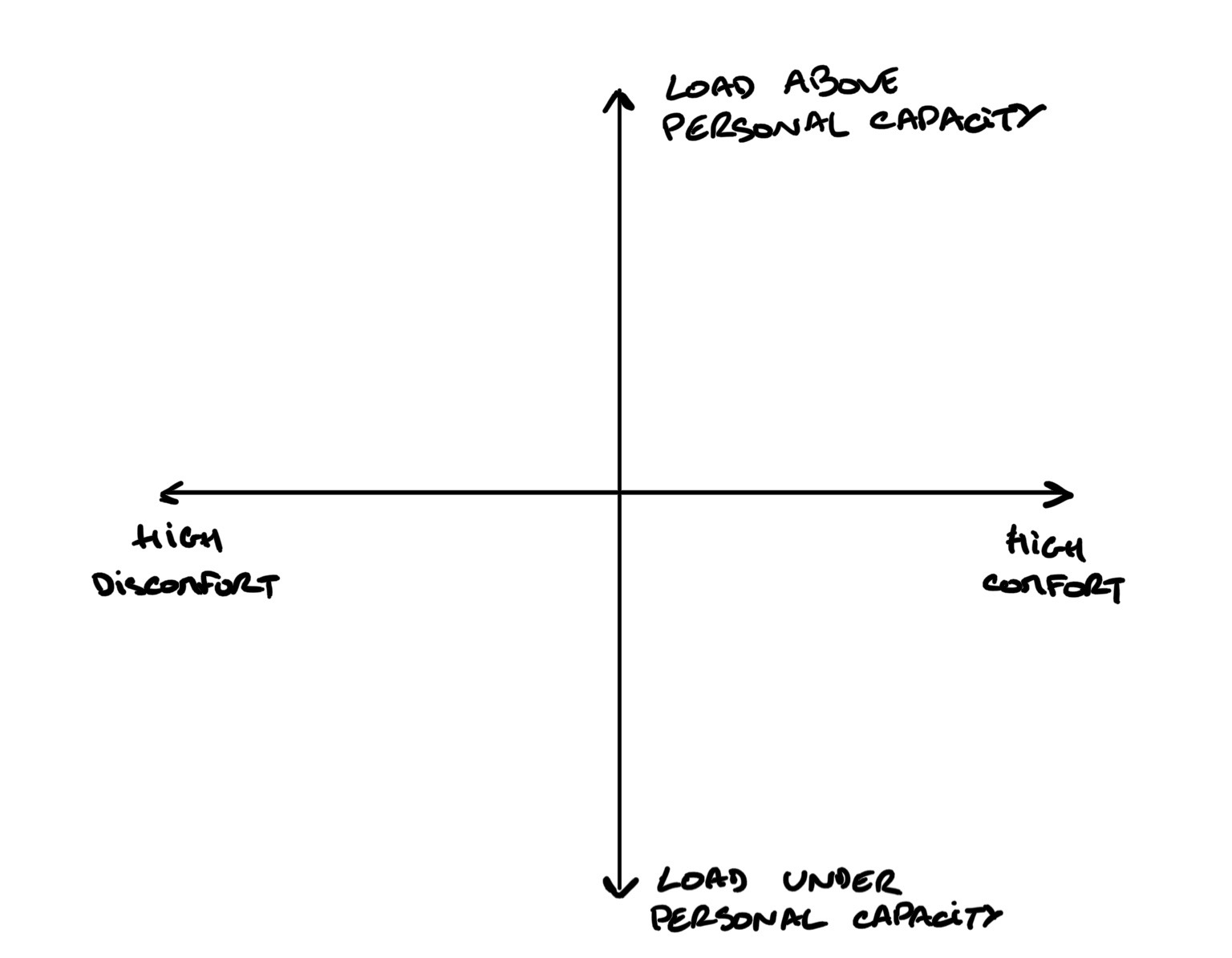

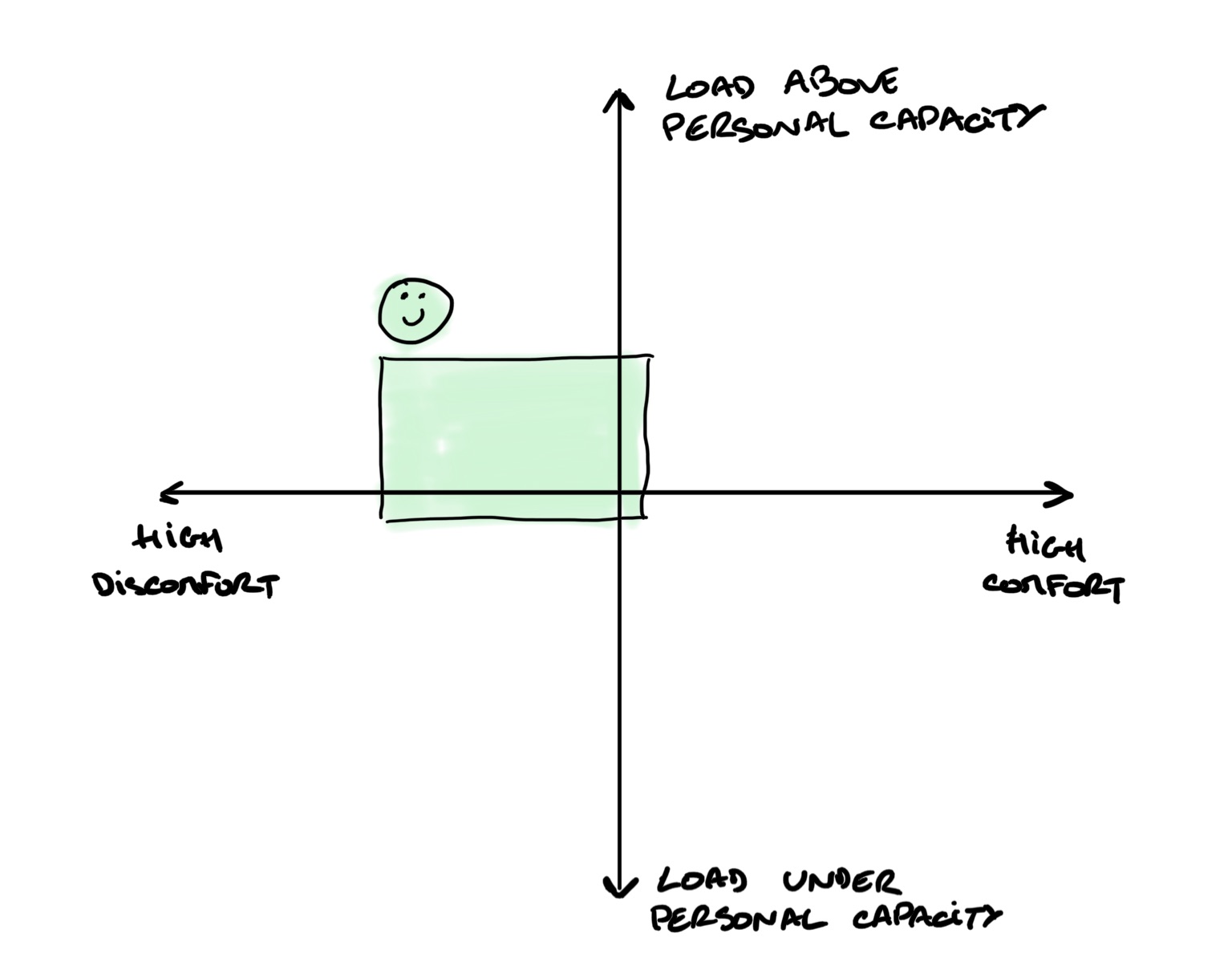

The way I picture my role as an engineering leader is to help my team succeed, whatever it takes. I constantly ask myself where our current bottleneck is (a concept you will be very familiar with if you’ve read The Phoenix Project or its inspiration, The Goal, which I both strongly recommend), and what is the most impactful thing I can do for the team.

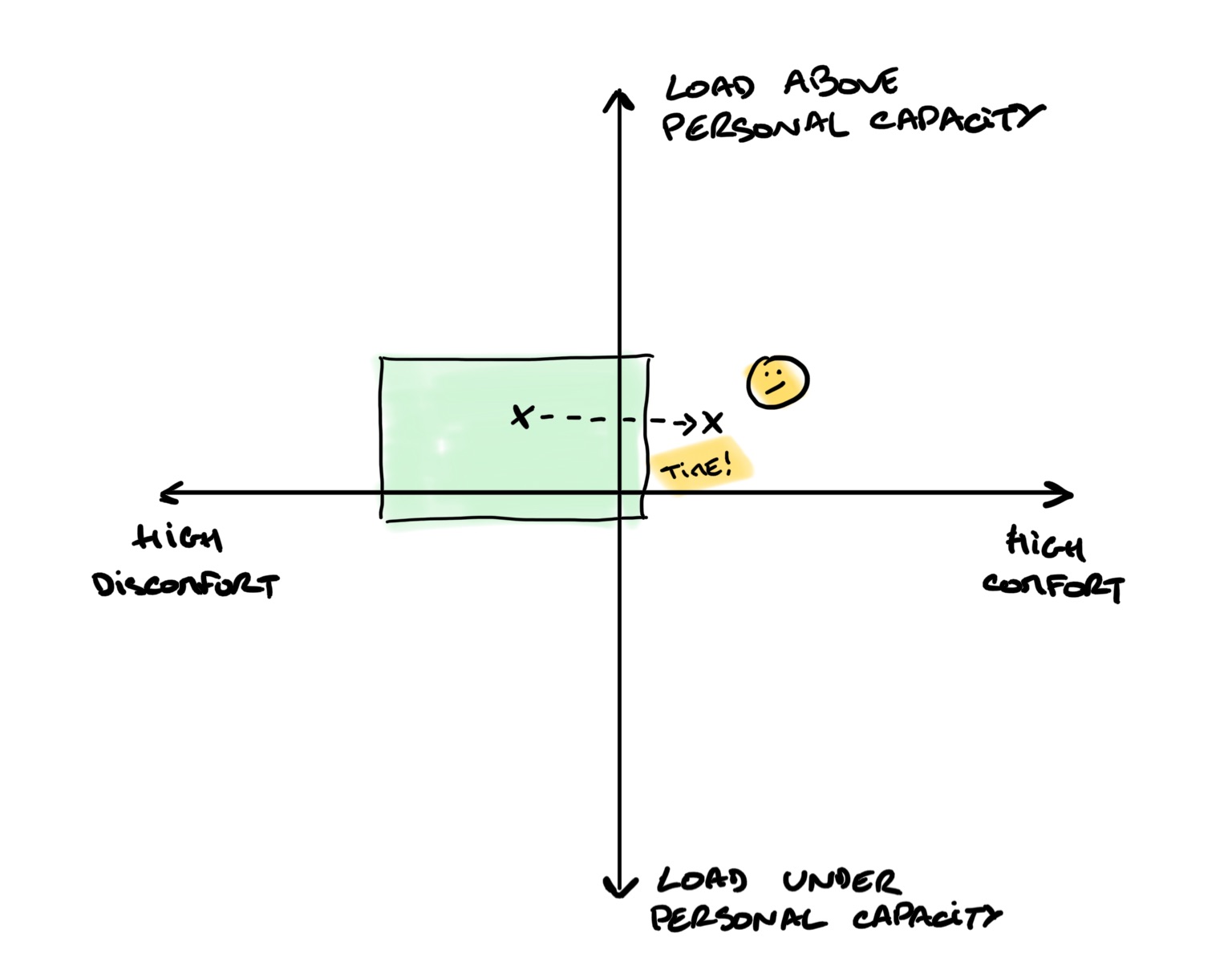

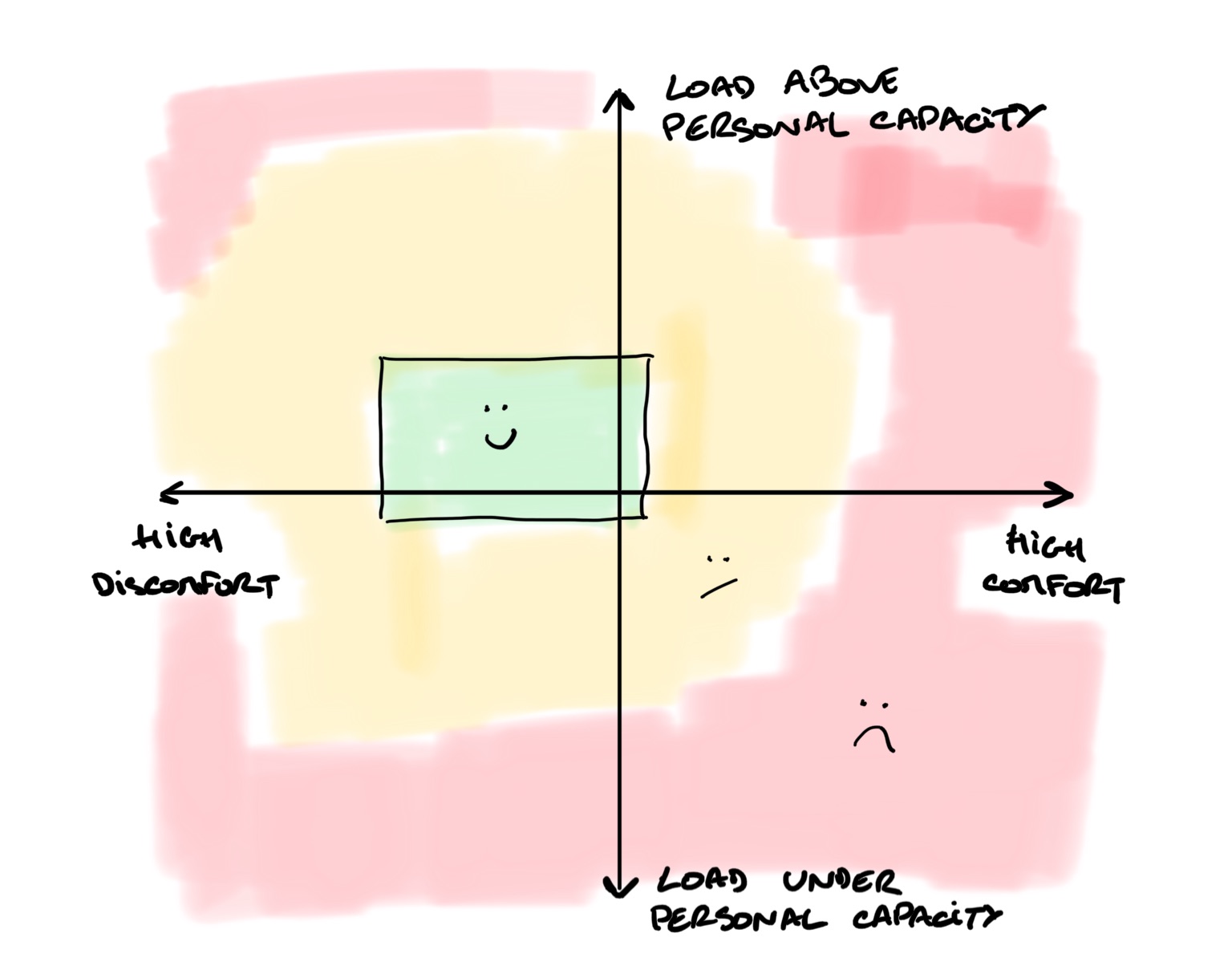

Here, what quickly appeared as bottlenecks are things that I’m sure most engineering leaders will recognize: insufficient clarity on our strategy causing a lack of alignment toward priorities, excessive work in progress, and a difficulty to move away from highly coupled historical systems all while keeping the business going. I cannot count how many times I’ve heard similar problems in the mouth of other engineering and product leaders. And for a good reason: this shit is hard. It’s hard because recipes in this area aren’t so easy to replicate (even though you can still find great and actionable books on such topics too). It’s also hard because unlike my earlier examples, things are not entirely in your hands.

This is where you have to go out to your peers, to managers in other departments, to your CEO, and define a path forward. It requires empathy (yes, again) but it also requires data. You’ll inevitably get asked why it is that everything cannot be delivered as asked, and frankly it’s a fair question to ask as an outsider to engineering. This is when I understood that quite often the best I could do to help my team succeed was to illustrate how their work fit the big picture and their struggles along the way.

Communicating on engineering activity

Getting visibility and communicating on the activity of engineering teams (whether to your CEO, CFO, VCs, or board) is notoriously difficult, and I don’t know of any proven and reusable recipe to do this right. I’ll share here how we’ve approached it, knowing that several other engineering leaders I talked to are doing some variation of that, but I’d be happy to learn of any better way. One thing to understand here is that the goal is not to create elaborate ways of saying no, but about finding ways to take part of a collective yes on achievable commitments.

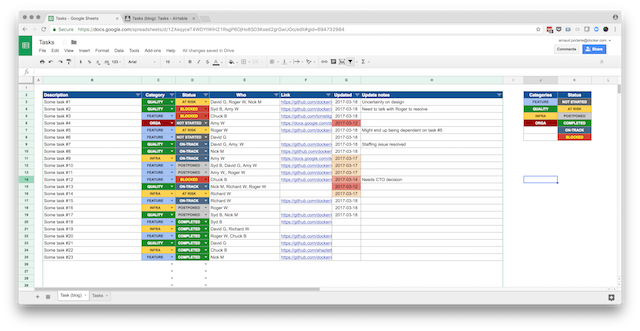

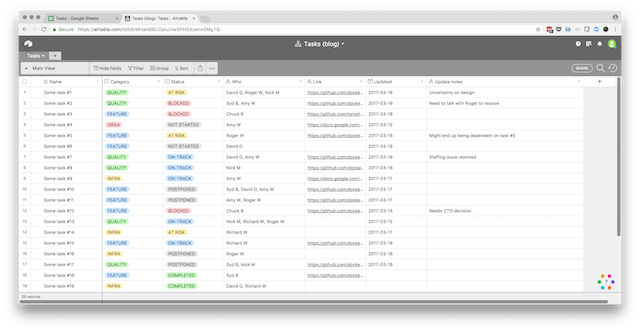

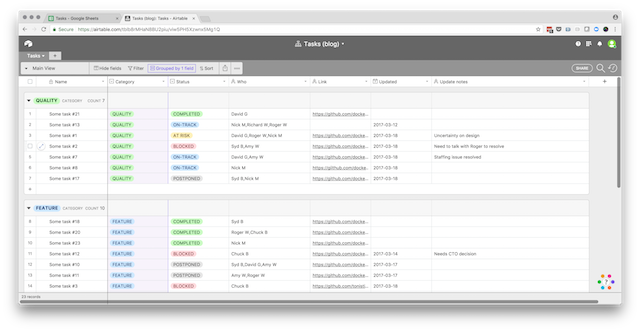

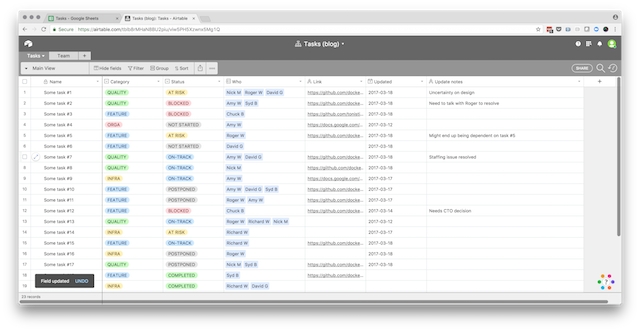

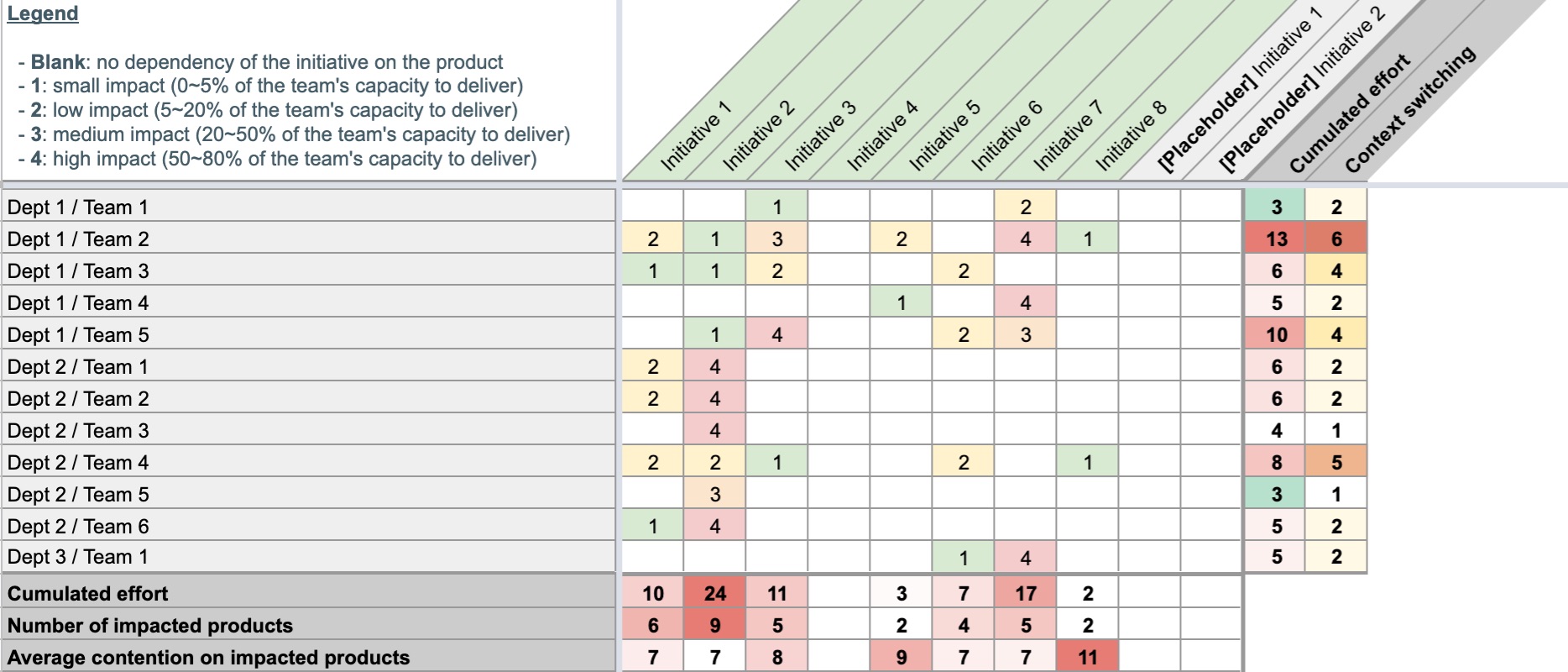

What we’ve done is a heat map of the activity of teams against different buckets of work, striving to stay away from technical jargon, and keeping it connected to desired business outcomes to the best of our ability. We’ve done it as anyone else would: with spreadsheets, duct tape, and many discussions. The template looks like this (in our case the number of individual product teams was over 50):

The table captures the allocation of work over a given period of time, and is assembled purely from discussions with Engineering Managers and Product Managers throughout the organization. The number in each cell is a very rough estimate of the effort dedicated by each team on each initiative, as indicated by the legend in the top left corner. It was deliberately sized in such a way that a given team may have a single contribution with a weight of 4, or two contributions with a weight of 3, but that more would likely indicate overcommit. It’s not intended to be exact, but to approximate the reality of our activity, and the accompanying challenges in terms of alignment and focus.

How you define the buckets of work (i.e., the columns) is naturally crucial. If you have adopted a product organization (such as described by Marty Cagan), chances are that a given team’s activity is going to be a mix of:

- Its own initiatives, made of the solutions to be experimented, deployed, or improved as collectively devised to address customer needs under the leadership of a Product Manager, and in accordance with some form company objectives. A split per company objective or top-level OKR can be interesting here where it makes sense.

- Some amount of top-down topics, which are typically already thought through and prioritized but require commitment from multiple teams to succeed. These can be either coming from business or tech itself (e.g., migrations).

The resulting table is certainly not rocket science but turned out to be quite the right level of granularity for many constructive discussions:

- Top-down initiatives are expected but having the majority of your product teams’ effort allocated to them is not a good sign: it begs the question of individual teams empowerment and the true autonomy of Product Managers.

- The more initiatives a given team is contributing to, the more likely it will fail delivering on some combination of them. One can argue that a high number of small-ish things is fine, but experience shows it rarely is: context switching has a cost, and the likelihood of one of these small-ish things to reveal itself as a Pandora’s Box cannot be ignored.

- For a given initiative, the number of impacted teams is of interest, if only as a proxy of the amount of coordination it will require, but more important is the existing contention of teams on its path. It sometimes takes a single team’s miss for an entire initiative to fail, and that risk grows as teams are spread thinner.

- It’s a good model for examining roughly the “compatibility” of an initiative to be potentially started with the existing workloads on the team, or the inverse results of stopping one.

- It’s a good model to support discussions of technical coupling and the value or architectural work (which could be the topic of an entire blog post itself) as it makes interdependencies more apparent.

Closing words

Engineering leadership has many facets and all companies are different, but one thing that I believe to be universally true is that good leadership is about helping your team succeed in any way you can. The biggest leverage won’t always be in your hands and might not be that much engineering related, but that doesn’t make it any less your responsibility. In this journey, being a good advocate for the team often starts by being able to communicate effectively on its activity and on its challenges.